ZIKA VIRUS

Zika virus is spread to people through mosquito bites. The most common symptoms of Zika virus disease are fever, rash, joint pain, and conjunctivitis (red eyes). The illness is usually mild with symptoms lasting from several days to a week. Severe disease requiring hospitalization is uncommon.

In May 2015, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) issued an alert regarding the first confirmed Zika virus infection in Brazil. The outbreak in Brazil led to reports of Guillain-Barré syndrome and pregnant women giving birth to babies with birth defects and poor pregnancy outcomes.

Symptoms,Diagnosis & Treatment Symptoms

- About 1 in 5 people infected with Zika virus become ill (i.e., develop Zika).

- The most common symptoms of Zika are fever, rash, joint pain or conjunctivitis (red eyes). Other common symptoms include muscle pain and headache. The incubation period (the time from exposure to symptoms) for Zika virus disease is not known, but is likely to be a few days to a week.

- The illness is usually mild with symptoms lasting for several days to a week.

- Zika virus usually remains in the blood of an infected person for a few days but it can be found longer in some people.

- Severe disease requiring hospitalization is uncommon.

- Deaths are rare.

Diagnosis

- The symptoms of Zika are similar to those of dengue and chikungunya, diseases spread through the same mosquitoes that transmit Zika.

- See your healthcare provider if you develop the symptoms described above and have visited an area where Zika is found.

- If you have recently traveled, tell your healthcare provider when and where you traveled.

- Your healthcare provider may order blood tests to look for Zika or other similar viruses like dengue or chikungunya.

Treatment

- No vaccine or medications are available to prevent or treat Zika infections.

- Treat the symptoms:

- If you have Zika, prevent mosquito bites for the first week of your illness.

Get plenty of rest.

Drink fluids to prevent dehydration.

Take medicine such as acetaminophen to relieve fever and pain.

Do not take aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), like ibuprofen and naproxen. Aspirin and NSAIDs should be avoided until dengue can be ruled out to reduce the risk of hemorrhage (bleeding). If you are taking medicine for another medical condition, talk to your healthcare provider before taking additional medication.

During the first week of infection, Zika virus can be found in the blood and passed from an infected person to another mosquito through mosquito bites.

An infected mosquito can then spread the virus to other people.

Zika Virus Disease Q & A

What is Zika virus disease (Zika)?

- Zika is a disease caused by Zika virus that is spread to people primarily through the bite of an infected Aedes species mosquito. The most common symptoms of Zika are fever, rash, joint pain, and conjunctivitis (red eyes). The illness is usually mild with symptoms lasting for several days to a week.

What are the symptoms of Zika?

- About 1 in 5 people infected with Zika will get sick. For people who get sick, the illness is usually mild. For this reason, many people might not realize they have been infected. The most common symptoms of Zika virus disease are fever, rash, joint pain, or conjunctivitis (red eyes). Symptoms typically begin 2 to 7 days after being bitten by an infected mosquito.

How is Zika transmitted?

Zika is primarily transmitted through the bite of infected Aedes mosquitoes, the same mosquitoes that spread Chikungunya and dengue. These mosquitoes are aggressive daytime biters and they can also bite at night. Mosquitoes become infected when they bite a person already infected with the virus. Infected mosquitoes can then spread the virus to other people through bites. It can also be transmitted from a pregnant mother to her baby during pregnancy or around the time of birth. We do not know how often Zika is transmitted from mother to baby during pregnancy or around the time of birth.

Who is at risk of being infected?

Anyone who is living in or traveling to an area where Zika virus is found who has not already been infected with Zika virus is at risk for infection, including pregnant women.

What countries have Zika?

Specific areas where Zika virus transmission is ongoing are often difficult to determine and are likely to change over time. If traveling, please visit the CDC Travelers' Health site for the most updated travel information.

What can people do to prevent becoming infected with Zika?

There is no vaccine to prevent Zika. The best way to prevent diseases spread by mosquitoes is to avoid being bitten. Protect yourself and your family from mosquito bites. Here’s how:

- Wear long-sleeved shirts and long pants.

- Stay in places with air conditioning or that use window and door screens to keep mosquitoes outside.

- Use Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)-registered insect repellents. All EPA-registered insect repellents are evaluated for effectiveness.

- If you have a baby or child:

- Treat clothing and gear with permethrin or purchase permethrin-treated items.

- Sleep under a mosquito bed net if you are overseas or outside and are not able to protect yourself from mosquito bites.

Always follow the product label instructions.

Reapply insect repellent as directed.

Do not spray repellent on the skin under clothing.

If you are also using sunscreen, apply sunscreen before applying insect repellent.

Do not use insect repellent on babies younger than 2 months of age.

Dress your child in clothing that covers arms and legs, or

Cover crib, stroller, and baby carrier with mosquito netting.

Do not apply insect repellent onto a child’s hands, eyes, mouth and cut or irritated skin.

Adults: Spray insect repellent onto your hands and then apply to a child’s face.

Treated clothing remains protective after multiple washings. See product information to learn how long the protection will last.

If treating items yourself, follow the product instructions carefully.

Do NOT use permethrin products directly on skin. They are intended to treat clothing.

What is the treatment for Zika?

There is no vaccine or specific medicine to treat Zika virus infections.

Treat the symptoms:

- Get plenty of rest.

- Drink fluids to prevent dehydration.

- Take medicine such as acetaminophen to reduce fever and pain.

- Do not take aspirin or other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

- If you are taking medicine for another medical condition, talk to your healthcare provider before taking additional medication.

How is Zika diagnosed?

- See your healthcare provider if you develop symptoms (fever, rash, joint pain, red eyes). If you have recently traveled, tell your healthcare provider.

- Your healthcare provider may order blood tests to look for Zika or other similar viral diseases like dengue or chikungunya.

- What should I do if I have Zika?

- Treat the symptoms:

- Get plenty of rest.

- Drink fluids to prevent dehydration.

- Take medicine such as acetaminophen to reduce fever and pain

- Do not take aspirin or other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. During the first week of infection, Zika virus can be found in the blood and passed from an infected person to another person through mosquito bites. An infected mosquito can then spread the virus to other people. To help prevent others from getting sick, avoid mosquito bites during the first week of illness. See your healthcare provider if you are pregnant and develop a fever, rash, joint pain or red eyes within 2 weeks after traveling to a country where Zika virus cases have been reported. Be sure to tell your health care provider where you traveled.

Is there a vaccine to prevent or medicine to treat Zika?

No. There is no vaccine to prevent infection or medicine to treat Zika.

Are you immune for life once infected?

Once a person has been infected, he or she is likely to be protected from future infections.

Does Zika virus infection in pregnant women cause birth defects?

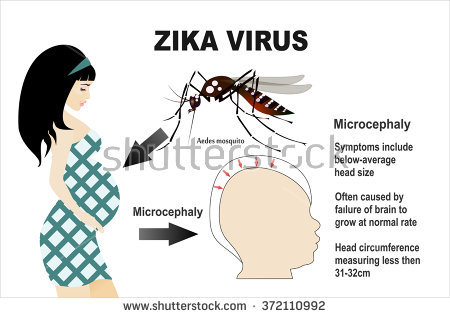

There have been reports of a serious birth defect of the brain called microcephaly (a condition in which a baby’s head is smaller than expected when compared to babies of the same sex and age) and other poor pregnancy outcomes in babies of mothers who were infected with Zika virus while pregnant. Knowledge of the link between Zika and these outcomes is evolving, but until more is known, CDC recommends special precautions for the following groups:

- Women who are pregnant (in any trimester):

Consider postponing travel to any area where Zika virus transmission is ongoing.

If you must travel to one of these areas, talk to your doctor first and strictly follow steps to prevent mosquito bites during your trip.

- Women who are trying to become pregnant:

Before you travel, talk to your doctor about your plans to become pregnant and the risk of Zika virus infection.

Strictly follow steps to prevent mosquito bites during your trip.

Does Zika virus infection cause Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS)?

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is a rare disorder where a person’s own immune system damages the nerve cells, causing muscle weakness and sometimes, paralysis. These symptoms can last a few weeks or several months. While most people fully recover from GBS, some people have permanent damage and in rare cases, people have died.

We do not know if Zika virus infection causes GBS. It is difficult to determine if any particular pathogen “caused” GBS. The Brazil Ministry of Health is reporting an increased number of people affected with GBS. CDC is working to determine if Zika and GBS are related.

Is this a new virus?

No. Outbreaks of Zika previously have been reported in tropical Africa, Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands. Zika virus likely will continue to spread to new areas. In May 2015, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) issued an alert regarding the first confirmed Zika virus infection in Brazil.

How many travel-associated cases have been diagnosed in the United States?

CDC continues to work with states to monitor the United States for mosquito-borne diseases, including Zika. In 2016, Zika became a nationally notifiable condition. Healthcare providers are encouraged to report suspected cases to their state or local health departments to facilitate diagnosis and mitigate the risk of local transmission. To date, local transmission of Zika virus has not been identified in the continental United States. Limited local transmission may occur in the mainland United States but it’s unlikely that we will see widespread transmission of Zika in the mainland U.S.

Should we be concerned about Zika in the United States?

The U.S. mainland does have Aedes species mosquitoes that can become infected with and spread Zika virus. U.S. travelers who visit a country where Zika is found could become infected if bitten by a mosquito. With the recent outbreaks, the number of Zika virus disease cases among travelers visiting or returning to the United States will likely increase. These imported cases may result in local spread of the virus in some areas of the United States. CDC has been monitoring these epidemics and is prepared to address cases imported into the United States and cases transmitted locally.